Juwayria Zahurullah ‘26

Winter Term 2025

Women in Liberal Arts, From Oberlin to Lahore

Over Winter Term 2025, Juwayria visited Lahore Grammar School (LGS) 55 Main, an all-girls primary to senior educational institution in Lahore, Pakistan. At LGS, she conducted classroom observations and teacher interviews in exploration of globally informed education practices and the mutual exchange of liberal arts values between Oberlin and Pakistan. She was able to build meaningful connections through engaged conversations with teachers and students about the importance of empowerment in education for women and girls.

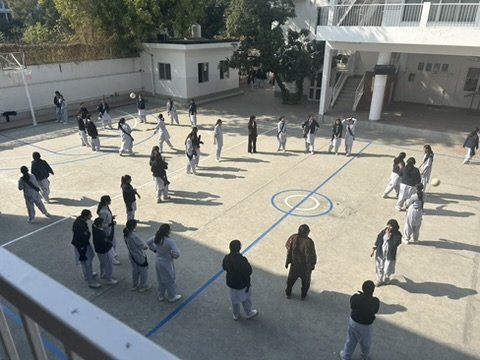

This Winter Term, I visited Lahore Grammar School (LGS) 55 Main in Lahore, Pakistan, to explore globally informed education practices and engage in the mutual exchange of liberal arts values between Oberlin and Pakistan. Prior to arriving at LGS, I had expectations of a school environment much different from what I observed. Given that it is a private, all-girls institution, I expected a certain level of strictness and formality that would contrast my experiences at schools I have attended and worked at in the midwestern United States. Upon my arrival, I found LGS to be an incredibly lively and creative learning environment, composed of confident and insightful women teaching a new generation of young female scholars.

While at LGS, I had the opportunity to observe two different grade 9 classrooms. I sat in for classes on subjects such as math, chemistry, biology, Urdu, English Literature, and World History. Observing these classes and seeing how students interacted and behaved reminded me of my own high school experience. I arrived at LGS on their first day back to in-person learning after classes were temporarily moved online while schools were closed due to poor air quality. As a student who completed more than half of my high school education with a hybrid of online and in-person learning, I recognized many familiar struggles during the adjustment back to in-person school. In some classes, students struggled to stay engaged with the material, while teachers reported low participation in online learning and correspondingly poor exam scores. Despite these evident struggles, I believe LGS is doing its best to navigate these unpredictable challenges, similar to how educational institutions around the world were forced to adapt quickly during the COVID-19 school closures.

I was notably impressed by the complexity of the humanities courses being taught to grade 9 students at LGS. I observed a heightened level of student engagement and interest during the humanities classes, as they typically included more spirited discussions where students were free to explain their own thoughts and reactions to the material. I was very lucky to have caught the World History class as they began their unit on Revolutions. In the first lesson, the students were asked how they understood the term “revolution” and what some specific characteristics or impacts of a revolution could be. Their answers varied greatly, but they all featured a highly impressive level of knowledge and complexity in thought.

I had the opportunity to speak with Meher Asif, LGS World History teacher, and ask her some questions about her background as an educator as well as the material she teaches. Ms. Asif graduated from LGS 55 Main and went on to study law at University College London. Alongside teaching at her alma mater, she currently practices environmental law. I was particularly interested in her unit on Revolution, and asked her to share more about how she teaches this content and what she feels are the most important takeaways. She explained how she begins the unit with the Reformation period in an attempt to provide students with an introduction to different thinkers and their philosophies. Ms. Asif explained that it was her priority for her students to understand diversity of thought and how it led to different periods within history, rather than simply memorizing timelines of events. In her teaching, she emphasizes ideas of life, friendship, and the role of institutionalized religion throughout history. She stated that she wants her students to “understand how [people] think, how it is different, and why it is ok.”

Ms. Asif also spoke about how she hopes for her students to understand revolution in terms of legacy rather than as isolated events throughout history and to understand the cycles of evil that exist between and leading up to revolutions. She reported that she rarely references or assigns material from the textbook in her classes because she recognizes the extreme Western bias that most textbooks are written with. She sees it as critical for educators to push back against the ideas of American exceptionalism that history curricula typically uphold in order to encourage open and free thinking in students.

I asked Ms. Asif about her thoughts on the importance of her students learning this material in relation to modern political climates, both globally and within Pakistan, especially in relation to the nation's history of colonization and its own struggles for independence. She emphasized the importance of patience in the fight for liberation, citing that short-lived revolutions almost always revert back. She hopes to instill the idea in her students that if they wish to change the system in which they live, they must first understand it, and then infiltrate it. We spoke about the prevalence of gender suppression in Pakistan and how women are constantly silenced or ignored in important conversations. The common dynamic that many Pakistani and other South Asian girls grow up witnessing is the “uncles”, or elder males, all in one room at a gathering discussing politics, while the women are in the kitchen doing domestic labor. Her hope is that her students become informed and confident enough to make space for themselves in these conversations and push back against the cultural and generational norm that women do not belong in discussions of topics such as politics.

In my future career as an educator, I hope to center these values and leave my students with a similar message to Ms. Asif’s. One of my main motivations in this project was to explore the concept of globally informed education practices in connection with liberal arts values. Ms. Asif’s value set and intentionality with how she engages with her students and their learning are exemplary to me of what globally informed liberal arts education should look like. Encouraging students to think, ask questions, and allow their confusion to bloom into confidence is the pinnacle of liberal arts education. Globally informed efforts to educate are those which encourage open thinking and dialogue from an array of perspectives, rather than the regurgitation of information from textbooks written with Western bias.

On my final day at LGS, I had the opportunity to speak with a group of grade 12 students who are interested in attending college in North America or Europe, with particular focus on engagement in college activism for Palestine. I spoke about my work in Students for a Free Palestine at Oberlin, particularly about the challenges of questioning progressiveness at liberal institutions, censorship and intimidation I have faced, and the importance of being steadfast in your dedication to a cause. I was also able to answer some very insightful questions from students about community building within activism work and what steps they can take to begin this work in their own communities.

I profoundly value the time I was able to spend at LGS, the conversations I had, and the insights I gained from the experience. I look forward to engaging in similar conversations and extensions of this work in the future.