Alumni Profile: Beatrice Camp '72

This week we are excited to feature Beatrice (Bea) Camp, class of 1972. Bea was a Shansi Fellow at Chiang Mai University in Northern Thailand from 1973 to 1976. Following her time as a Shansi Fellow, Bea went on to have a long and distinguished career in the Foreign Service. She served as the Consul General in both Shanghai and Chiang Mai, along with positions in Beijing, Bangkok, Indonesia, Mongolia, Hungary, Sweden, as well as Washington, DC. Currently, Bea serves as the editor of American Diplomacy, an online journal offering insight and analysis from foreign affairs practitioners and scholars.

Bea with Secretary of State John F. Kerry

During college you worked at the Oberlin Review and were interested in pursuing journalism before joining the Foreign Service. How did you decide to apply for a Shansi Fellowship, what were some favorite memories, and how did it affect your career path?

I took the Foreign Service exam after graduating in 1972, but wasn’t ready to pursue it at that point. A year later Shansi opened new opportunities, expanding programs beyond Taiwan and India. Although I was offered the chance to go to Indonesia, I held out for Chiang Mai University in northern Thailand. In September 1973, I set off for Bangkok on Pan Am’s round-the-world eastbound flight, making stops along the way in Stockholm and Budapest. As it happened, I later served in embassies in both cities. With several weeks before the university semester started in Chiang Mai, I settled down in Bangkok to study Thai at AUA (American University Alumni Association). This too foreshadowed my future -- as one of the U.S. Government’s binational centers, AUA later became a significant part of my assignment at Embassy Bangkok. During my second week of study, I arrived at AUA to find the gates locked. A student protest in the center of town had turned bloody and the entire city was locked down. That October 1973 uprising was an eye-opening beginning. My two-and-a-half years teaching at Chiang Mai University marked the height of the Thai student revolt against dictatorial government. Thirty years later, I was Consul General in Chiang Mai when a military coup brought down Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra and armored personnel carriers hovered at the consulate gate. It helped to have historical perspective on these happenings.

At the university, I was lucky to follow in the footsteps of Geoff DeGraff, who had gone the previous year as an experimental rep. We celebrated Thanksgiving together by cooking omelets on a hotplate. Despite the minimal meal, and the fact that we had to work that day, it felt festive because we were together and sharing a meal. Although my Oberlin fellowship ended in 1975, I stayed on until the next spring. During the Thai university holiday in April, I arranged to visit Shansi fellows in Taiwan, Japan, and Korea, booking my flight on Air Vietnam before switching to a cheaper ticket on Japan Airlines. Saigon fell while I was traveling; I wondered what would have happened to my Air Vietnam tickets when the South collapsed that month. My most memorable stop was Taiwan’s Tunghai University, where the Shansi program had moved after the Communist takeover on the mainland. I never imagined I would be living in Taipei seven years later studying Mandarin at the U.S. foreign service language school.

It was tremendously exciting to return to Chiang Mai 30 years later. As the chief U.S. diplomat in northern Thailand, I led a consulate with 30 American and 50 Thai staff. We reported on political, economic and social developments in the Burma, Lao and China border areas, handled visa and American citizen services, ran cultural and educational programs, and dealt with issues ranging from narcotics to Burmese exiles. Given my previous affiliation with the university, I took a special interest in education and exchanges. Chiang Mai was much changed when I returned in 2004, with more traffic, more tourists, more restaurants, more pollution, but I could still ride my bike out to the university and enjoy remembering my days on campus.

Bea on a trip with her students

You also served in China, first in Beijing and later as Consul General in Shanghai; what was it like to be there twice, 25 years apart?

Beijing was my first foreign service post. As a new officer, I did a bit of everything, including editing articles for our one-country magazine Jiaoliu, helping with the press during President Reagan’s visit, and providing materials for the growing number of American teachers flowing into China. Having been on the Shansi board in 1980 when Oberlin reestablished the connection with the original school in Taigu, now the Shanxi Agricultural University, I reached out to connect with the four fellows there and invited them to Beijing for Thanksgiving dinner. My husband and I also visited them. As diplomats we were restricted to 25 kilometers from the center of Beijing, but we gambled and boarded a train to the provincial capital of Taiyuan, where a car sent by the university met us. Although we could have been in trouble from both the Chinese authorities and the embassy for traveling without official permission, the SAU foreign affairs office waited until after we went to bed in the Shansi fellows’ cottage to come ask for the required registration. Our Shansi hosts explained that we had turned in for the night; the foreign affairs office politely responded they didn’t want to disturb us and left -- our Oberlin connection earned us protection. We weren’t busted by the Chinese or reprimanded by the embassy and I got to visit the old Ming Hsien campus.

Twenty-five years later, as Consul General in Shanghai, we again hosted the Shansi fellows every Thanksgiving, although we didn't make it to SAU again. The country had changed immensely since our departure from Beijing in 1985. This time, we had another presidential visit as Barack Obama made Shanghai the first stop on his first visit to China. Shanghai also hosted the 2010 expo, the largest ever world’s fair. Our consulate was very much involved with the USA Pavilion, which welcomed seven million Chinese visitors as well as celebrities such as Hillary Clinton, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Herbie Hancock, and Big Bird. But student exchanges still remained a favorite of mine.

What do you think is unique about a Shansi Fellowship and what advice would you give to those interested in a foreign service career?

I can’t speak for today’s fellows, when there are so many more opportunities abroad, but I always felt Shansi provided the right amount of independence bolstered with distant support. Although my Peace Corps friends had similar experiences, they also had more rules to follow. I also appreciated the long history behind the fellowship. Despite periodic protests on campus over the Memorial Arch and what it represents, I found the stories of missionaries who had worked in China and Thailand compelling, especially as I knew that several of our most knowledgeable ambassadors and China hands were children of missionaries, not to mention Oberlin alum John Service. Shansi’s roots in China also gave me a feeling of connection over the generations. One testimony to the association’s role in advancing Asia-related careers is the fact that I was not the first Shansi alum to serve as Consul General in Shanghai. That honor belongs to Doug Spelman, who preceded me by six years. Shansi is great preparation for a foreign service career; both require adaptability and a sense of adventure. Learn as much as you can and take advantage of any training. Study the history, culture, and language. Invite U.S. diplomats to your site and help them appreciate the citizen diplomacy involved. Get around as much as possible; nothing replaces getting to know people and meeting face to face.

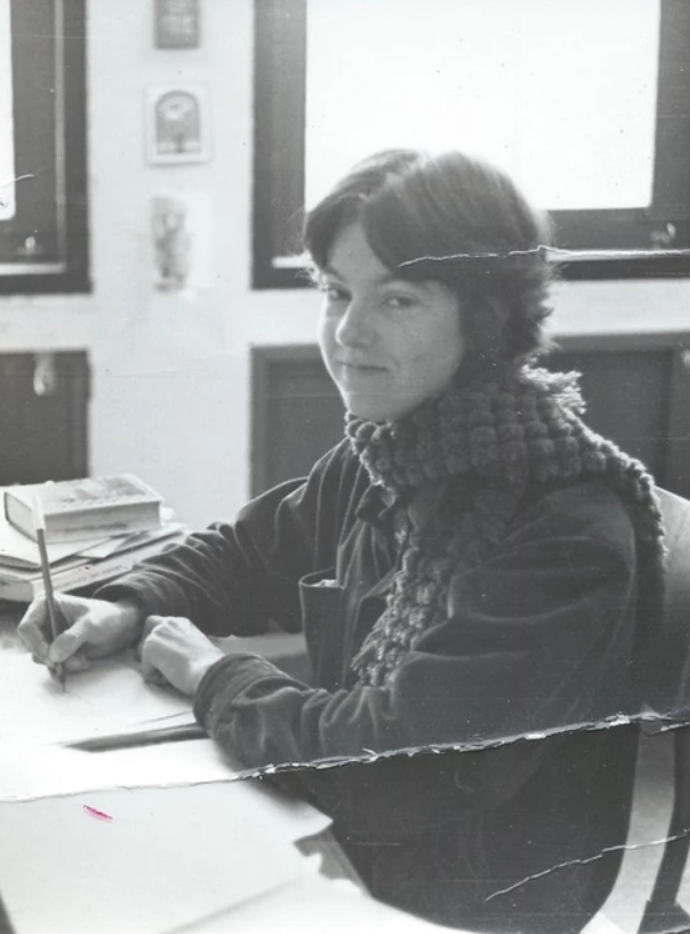

Bea grading papers at Chiang Mai University in 1974