Stories of My Grandmother

By Louise Edwards ‘16, Shanxi Agricultural University (2016-2018)

Teaching oral English at Shanxi Agricultural University, I’m often thinking of ways for my students to practice their speaking. Sometimes as their homework I ask them to send me voice messages on the app Wechat — one of the most common messaging apps in China. In one of these assignments, I asked students to tell me a story that their parents or grandparents often told them. Some retold fables or fairytales that were familiar to me such as “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” or “Little Red Riding Hood.” Other students told me Chinese legends that I had never heard before such as “孔融讓梨” (Kong Rong Giving Up Pears) and“ 卧冰求鲤”(Lying Down on the Ice to Fetch Fish).

Many of the students talked about Shanxi Province and their families’ farming or working class backgrounds. For example, my student 曹培杰 (aka Erin) said, “My mother told me there were six children in her family and her mother died when she was a little girl. There was no money for her tuition so she had to get out of school to help do some housework. My mother often teaches my brother and I to cherish the chance of learning.”

Like Erin, I never knew either of my grandmothers because they died before I was born. Yet, I’ve always felt close to both of them because I’ve gotten to know them through stories my family has told me. Like many of my students’ grandmothers, both of my grandmothers valued education. My mom’s mom Mary Louise Ritzel, whose relatives had immigrated to the U.S. from Alsace-Lorraine, was one of the few women in her Pittsburgh neighborhood to have earned a PhD. She became a social worker. My dad’s mom Vee Tsung Ling, who grew up on鼓浪屿 (Gǔlàngyǔ), an island off of Xiamen in southern China, immigrated to the U.S. to study piano at Duke University.

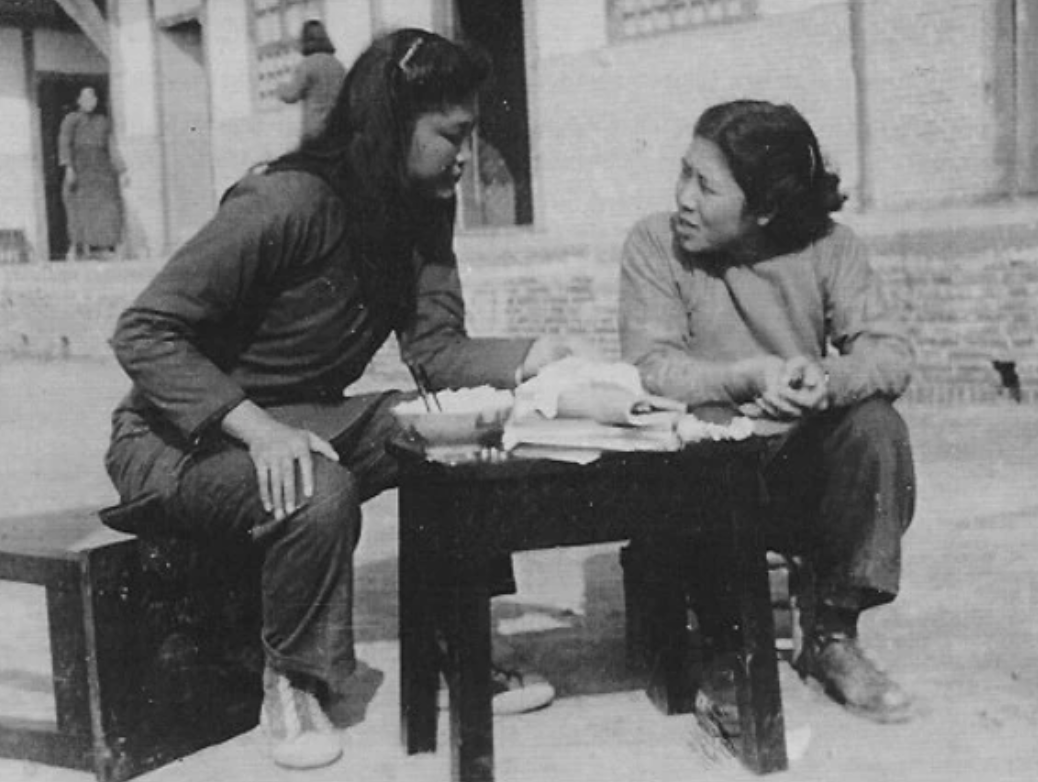

She later taught Chinese language courses at Yale and also worked for Oberlin-in-China as the dean of women at Ming Hsien school in Chengdu, China. Later, Oberlin-in-China was renamed Oberlin Shansi and the Ming Hsien school became Shanxi Agricultural University, the university I teach at. (At the time my grandmother was a dean of women at Ming Hsien from 1949-1950, the campus had moved out of Shanxi Province to Chengdu to avoid conflict between the Chinese Nationalists and Communists. So, different location but same school.)

My grandmother, Vee Tsung Ling (right), talking with a student at Ming Hsien school.

My student, 杨嘉瑞 (aka Rose), also told a story about her grandmother valuing education. She said, “My grandmother always told a story about my aunt. When my aunt was young, she always worked hard. One day, before my grandmother went to work, she told my aunt to remember to turn off the water when it boils. My aunt was studying and she said okay. But, when my grandmother came back, the water had been boiling and the pot was empty. My grandmother has told me this story more than 5 times. She means she wants to encourage me to study very hard.”

Another one of my students, 陈媛, told me about when her grandparents fell in love, “When he was young, my grandfather was very handsome. He was a soldier when he was young. He went to Sichuan province with the army. Sichuan Province is far away from Shanxi Province. In that province, he was very popular in the army not only because he was handsome, but also because he had a lot of ability. Then, my grandmother was 18 years old and fell in love with my grandfather. My grandmother ignored her parents’ advice and married my grandfather and moved back to Shanxi province with him. Now my grandparents are still living a healthy and happy life.”

Mary Louise’s mom also did not want her to marry my Irish grandfather, John McDonald. When he came to the house to see Mary Louise, he would yell, “I’m going to marry your daughter.” And her mother would yell back, “You will not!”

When Vee and my grandfather, Richard Edwards met, my grandfather was my grandmother’s student in her Chinese language class at Yale. My grandfather would tell me that on their first date, they met each other on the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of art. When asked what they say at the museum, he responded, “I don’t know, I was too taken with my companion to notice.”

Though there are numerous stories I could tell you about my grandmothers, if I had to pick one, I might tell you about Vee’s first home. Having heard so much about my grandmother, I wanted to see where she grew up. So during my winter vacation, my sister and I, along with our Oberlin friend, took a train to Xiamen and then a ferry to 鼓浪屿

Going to 鼓浪屿, you can smell the sea green air long before the ferry docks. The ferry pier is loud and sweaty. Tourists swarm toward their hotels or the nearest 5-star attraction. The quietness doesn’t set in until hours later, wandering past the ruins of an old government building: There are no cars on the island. No honking, no sidestepping motorbikes, no pollution. Here the sky is always blue even when it’s raining.

A view of 鼓浪屿。

For many years, 鼓浪屿 was the only international settlement in China. After China lost the First Opium War in 1842, the Qing Emperor, 道光帝, signed one of several of the Unequal Treaties in which Great Britain had no obligations to China, while China had many. British soldiers remained on 鼓浪屿for a few years to ensure the Qing emperor would pay reparations and 13 countries received extraterritorial privileges on the island: Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, Japan, Germany, the United States, Spain, Denmark, Portugal, Sweden, Norway, Austria, and Belgium. As the British soldiers were leaving, in came the foreign officials, merchants, missionaries. The consulates and churches. The red-roofed villas and pianos.

A whole island of pianos. In the piano museum, some are ornately painted red and gold with showy flowers, some are sleek and black, and others are wooden uprights that missionary wives used to run their ghostly fingers over. Of course, now it makes sense why my grandmother studied piano.

A “corner piano” from the piano museum on 鼓浪屿.

Before coming, my sister and I didn’t know this history. All we knew was the story of a family mansion. We had the address to the mansion and an old telephone that may or may not be correct number of a relative from 鼓浪屿.

The first day, we found the mansion. To our surprise, it was at the center of the island. Street vendors sold soft tofu and mangoes in front of the gate and there was even a plaque that told the history of the house. The front yard was filled with yellowed grass and paint was peeling from the railings. The mansion could be abandoned if not for the clothes hanging from the second floor balcony and the towels on the clothesline.

The gate was locked, so we decided to try the telephone number. A woman answered, perhaps the wife of our relative, and she gave us a different telephone number to try. The second time, a man picked up. He was, in fact, the person we were looking for. That day he was in Xiamen on business, but the next morning he kindly promised to come back and show us the house.

The family mansion on 鼓浪屿.

叔叔 unlocks the mansion’s back door and we step inside. The first floor is gloomy, although supposedly when the front hall is open the stain glass sparkles. I can only imagine the colored light dancing on the walls. All the rooms off of the hallway are closed off for safety reasons.

Piano music plays from an upstairs room and a shiver runs down my spine. My grandmother has to be here, for who else would be playing. For a moment I can imagine her old potter’s hands rounded over the keys, her eyes closed playing from memory. Even though she passed away over 20 years ago, it’s not until the music stops and a braces-faced teenager greets us at the top of the steps that I realize it’s not her. Instead, it’s our cousin who attends a music school on the island.

This island — historically an international hub and now a tourist destination — is a strange contrast to Shanxi Province. In Shanxi, historically, foreign missionaries and Chinese Christians were killed during the Boxer Rebellion, an anti-foreigner anti-imperialist movement. Those killed included Oberlin missionaries and Chinese Christians in Taigu. The Ming Hsien school was created to memorialize their deaths and the missionaries killed remain here, buried on the campus. Now, there are still very few foreigners in Shanxi Province — perhaps only about 30 in Taigu, a town of 300,000.

Because of this, many people are curious about foreigners. When I walk down the street, I can hear many people talking about me. Some point. Others take photos on their phones. Some simply stare. It is strange to feel so foreign in a country that I am also from.

On the first day of class, I find myself introducing my grandmother to my students. I show them the slide of her teaching at Ming Hsien school. I ask them half joking and half serious, “Do I look like her?”

***

On 鼓浪屿, climbing the stairs to the second floor of the mansion, more light comes in from the windows. We stand on the balcony with 叔叔 and our cousin, eating candies and looking out at the view. My grandmother is both here and departed. Just as I feel home and not home, Chinese and not Chinese, a tourist and not a tourist.

叔叔, our cousin, me, and my sister on the balcony of our family’s house in 鼓浪屿.